Share this

By Ezra Klein

Washington Post Staff Writer

Saturday, December 18, 2010; 3:58 PM

Saturday, December 18, 2010; 3:58 PM

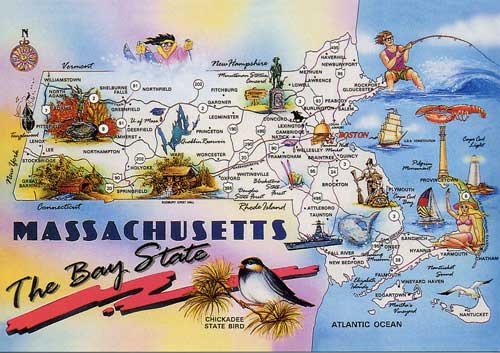

So rather than sit around and wonder about a world without an individual mandate, let’s talk about a world that has one. We don’t have to go into hypotheticals to get there. We just have to go to Massachusetts.

In 2006, then-governor Mitt Romney signed a major health-care reform bill into law. “An achievement like this comes around once in a generation,” he said. “Today, Massachusetts is leading the way with health insurance for everyone, without a government takeover and without raising taxes.”

Romney was right about all of that. And national Democrats took notice. The health-reform bill President Obama signed into law this year was explicitly based on the Massachusetts reforms. The theory was this: A plan that a Republican governor could sign into law would be a plan that could attract Republican votes.

The theory was wrong. An approach to universal coverage that represented “health insurance for everyone without a government takeover” when it was signed by a Republican governor in Massachusetts was spun by congressional Republicans as the missing final chapter of “The Communist Manifesto” when Democrats tried to scale it nationally.

Given that the plan was enacted anyway, it’s time to check in on how Massachusetts is doing. And the answer, basically, is pretty well. This week, the state’s health and human services agency released the results of a new, independent survey examining coverage in Massachusetts. More than 98 percent – 98 percent! – of the state’s residents now have health insurance, as do more than 99 percent of the state’s children.

Remarkably, those numbers have gotten better in recent years, with the number of uninsured residents in the state falling to 1.9 percent in 2010 from 2.6 percent in 2008. That’s very unusual. Normally, the ranks of the uninsured swell during recessions as people lose their jobs and states cut back on public programs to balance their budgets. Nationally, the number of Americans who are uninsured rose to 16.76 percent in 2010 from 14.8 percent in 2008, according to Gallup.

That Massachusetts’s reforms have survived, and even prospered, in this economic environment has left the law’s architects feeling vindicated. “The goal of the law was covering people,” says Jonathan Gruber, an MIT health economist who worked on the legislation, “and it couldn’t have gone better.”

By and large, that’s reflected in the polling. The Massachusetts reforms have consistently polled between the high-50s and mid-60s. Perhaps their most impressive showing came amidst now-Sen. Scott Brown’s candidacy, when a Washington Post-Kaiser-Harvard poll found that even though a majority of Massachusetts voters disapproved of the national reform effort, a majority of them – and even a majority of Brown’s supporters – approved of the Massachusetts law.

The law does have its problems. In particular, it was not designed to control costs. “That’s one of the areas where the federal bill is just better than the Massachusetts bill,” Gruber says. So costs in the state have continued to rise – with one notable exception that has a lot to say about our current debate over the individual mandate.

In Massachusetts, that market has worked better than expected. According to data from America’s Health Insurance Plans, the largest health insurer trade group, premiums for that market have fallen by 40 percent since the reforms were put in place. Nationally, those premiums have risen by 14 percent.

There are a couple of reasons for Massachusetts’s success. One is that the market is more transparent, and so insurers are competing more aggressively against one another. Jon Kingsdale, who ran the new health-care market, notes that the lower-cost plans have been much more popular than the higher-cost plans. The bigger reason is that the individual mandate – plus the combining of individual and small firms in the same insurance market – brought healthier, younger people into the mix, which brought average premiums down for everybody.

All is not roses and waterlilies for Massachusetts, of course. The reforms didn’t address a number of problems: The state had, on average, the highest health-care costs before reform, and it has the highest health-care costs today. (There are a variety of reasons for this, many of them having to do with the power of the state’s renowned hospitals.) Waiting rooms were overcrowded before, and they’re overcrowded today. And there are places where the reforms didn’t work as hoped. Predictions that expensive emergency room visits would drop now that people could go to the doctor have not been borne out.

The national law is better on at least some of those counts. It has provisions to expand the medical workforce, particularly the ranks of general practitioners. It has a slew of cost-control efforts, including a tax on expensive health insurance plans, an independent board able to make cost-cutting reforms to Medicare, a vast array of changes to the health-care delivery system, changes designed to get us away from paying for volume and toward paying for quality and much more.

But the reality is that there’s one way in which it could get much worse: if Republican judges strike out the individual mandate, and Republican congressmen refuse to work with Democrats on a replacement. In that world, the law can limp along, and it will still cover tens of millions of Americans, but premiums will be higher, the insurance markets will be less competitive and many of the bill’s cost controls will not have the chance they need to work.

So repeat after me, “Justice Kennedy: You’re getting very sleepy . . . ”

Share this

Contact Us

Have questions? Send us a private message using the form below.